Editor’s Note: This is Part I of a two-part series. Part II is now up and you can see it here.

The media and blogosphere are buzzing with panic about an imminent “deflationary spiral” — a lengthy, self-reinforcing, and intractable decline in prices that will usher in pain not seen since the Great Depression.

The fear is that if declining demand for goods and services forces companies to charge less, they will fire workers or reduce wages, thus forcing a further reduction of economy-wide demand. Demand for goods is further reduced because while wages are dropping, the amount of debts owed remains the same, so people have to spend a higher proportion of their wages on debt service. Along the way, the thinking goes, consumers will see that prices are dropping and accordingly delay their purchases, putting yet more downward pressure on prices. The result is an ever-growing spiral of decreasing economic activity and falling prices.

There is something to this line of thinking, but it ignores a major piece of the puzzle: prices are denominated in dollars. And today’s dollar differs from the currency that kept score during the Depression of the 1930s in two very important ways: that our government can create as many new dollars as it sees fit, and that it sees fit to create an awful lot of them.

While this state of affairs offers many reasons for concern, the risk of a protracted deflationary spiral shouldn’t be one of them.

Mainstream economics’ big takeaway from the Depression is that deflation must be prevented at all costs. Our fiscal and monetary leaders have fully embraced this view. And unlike their Depression-era predecessors, they can carry this goal out by virtue of their ability to push up dollar-denominated prices by creating literally endless amounts of new money from nothing.

The power of this money minting ability seems to be inadequately appreciated. The authorities could, if they wished, deliver several million dollars of freshly-printed money to every single household in the country if they decided to do so. Under this pure paper money system, it is absurd to suggest that the government cannot create inflation. The only question is whether they are sufficiently motivated to do so. For reasons I will explain below, I have little doubt that they are.

Definitions

First, I must briefly deal with the definitional problem inherent in this topic. The word “deflation” is used by some people to describe a generalized decline in prices. To others, the word describes a decline in the amount of money circulating in the economy. The word “inflation” correspondingly refers to an increase in prices or an increase in the money supply, depending on whom you ask.

This dual definition has caused a lot of confusion in the inflation-deflation debate. I don’t particularly care which is the “right” definition, but I do think it’s important to understand that these are two separate (though related) phenomena. Where necessary, this article will specify which type of inflation or deflation is being discussed. (If no specification is made, then I am referring to both types — this is a reasonable shortcut given that changes in the money supply are a major causal factor in price changes).

I believe that the current monetary system, political climate, and prevailing analytical framework are incompatible with a prolonged period of either monetary or price deflation. This thinking is based on two fundamental premises:

- That the monetary and fiscal powers that be are extremely motivated to prevent a lengthy deflation.

- That they are entirely capable of doing so.

The Government Can Inflate

Let’s begin with the second premise first. It should be pretty much beyond argument that in a pure fiat money regime, a sufficiently motivated government can always cause monetary inflation. And a sufficient amount of monetary inflation can always be depended upon to cause price inflation.

To use an example that is extreme to the point of absurdity, but that illustrates the assertion, imagine if the government sent every household in the United States a check for $10 million, with the proceeds to be supplied by the creation of new money by the Federal Reserve. This would by definition be monetary inflation, as the supply of money in the economy would skyrocket. And there is just no doubt that this vast increase in money held by the public would cause rampant price inflation as each household rushed out to spend its newly acquired dollars. It wouldn’t matter whether the economy was in recession, or whether the banking system was deleveraging, or pretty much anything else for that matter. Inflation would follow.

If exaggerated thought experiments aren’t your thing, consider the following excerpts from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s seminal 2002 speech about preventing deflation (emphasis mine):

Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation…

So what then might the Fed do if its target interest rate, the overnight federal funds rate, fell to zero? One relatively straightforward extension of current procedures would be to try to stimulate spending by lowering rates further out along the Treasury term structure—that is, rates on government bonds of longer maturities…

Lower rates over the maturity spectrum of public and private securities should strengthen aggregate demand in the usual ways and thus help to end deflation. Of course, if operating in relatively short-dated Treasury debt proved insufficient, the Fed could also attempt to cap yields of Treasury securities at still longer maturities, say three to six years. Yet another option would be for the Fed to use its existing authority to operate in the markets for agency debt (for example, mortgage-backed securities issued by Ginnie Mae, the Government National Mortgage Association)…

Therefore a second policy option, complementary to operating in the markets for Treasury and agency debt, would be for the Fed to offer fixed-term loans to banks at low or zero interest, with a wide range of private assets (including, among others, corporate bonds, commercial paper, bank loans, and mortgages) deemed eligible as collateral…

Each of the policy options I have discussed so far involves the Fed’s acting on its own. In practice, the effectiveness of anti-deflation policy could be significantly enhanced by cooperation between the monetary and fiscal authorities. A broad-based tax cut, for example, accommodated by a program of open-market purchases to alleviate any tendency for interest rates to increase, would almost certainly be an effective stimulant to consumption and hence to prices…

A money-financed tax cut is essentially equivalent to Milton Friedman’s famous “helicopter drop” of money…

Of course, in lieu of tax cuts or increases in transfers the government could increase spending on current goods and services or even acquire existing real or financial assets. If the Treasury issued debt to purchase private assets and the Fed then purchased an equal amount of Treasury debt with newly created money, the whole operation would be the economic equivalent of direct open-market operations in private assets…

Back when this speech was delivered in 2002, Bernanke’s policy suggestions for curing a deflation seemed incredibly radical. Today, as I will discuss below, they have largely become the norm.

I do not deny that there are deflationary forces in play, or that a prolonged deflation would likely result if those forces were allowed to run unchecked. Rather, my assertion is that it is well within the capabilities of our government to overcome the deflationary forces should they choose to do so. They have the ability to create money and force it into the economy via multiple vectors. To the extent that their efforts do not overwhelm the forces of deflation, they can do more of the same, to an ever more dramatic extent, until their goal is achieved.

This is simply a fact of life in a monetary regime in which new money can be created out of nothing.

The Government Wants to Inflate

A sufficiently motivated government with a fiat currency system can always inflate. That leaves the question of whether our particular government, with our particular monetary system, in our particular political, economic, and analytical climate, will be sufficiently motivated to cause inflation even if they are forced to resort to the radical monetary policies and open currency debasement described in the prior section. I believe the answer is a resolute “yes.”

The reason I can be so confident is that the government (and I include the Federal Reserve in that designation) has already shown that this is so. Chairman Bernanke has already followed through on many of the policies threatened in his 2002 speech. Our monetary leaders at the Fed have:

- slashed rates to very near 0%;

- begun a program to monetize (i.e. created new money in order to buy) “large quantities” of mortgage-backed securities and agency debt;

- lent directly into the commercial paper market;

- suggested that they will directly monetize Treasuries;

- taken over or guaranteed the obligations of several huge and bankrupt financial institutions;

- created various facilities to take assets of questionable value from banks and trade them for Treasuries;

- created yet more facilities to goose consumer and business credit by monetizing asset backed securities; and

- nearly doubled the size of the monetary base (the “raw material” of money creation, over which they have direct control) within a few months.

This is in addition to the efforts of the Congress and Treasury, which include among many other expenditures:

- the infamous TARP program to buy stakes in banks and their toxic assets;

- expansion of FDIC protection;

- money market fund guarantees;

- the automaker bailout;

- Hope Now and other housing bailout attempts;

- the now laughably small early-2008 stimulus package; and

- soon enough, the vast stimulus programs being proposed by President Obama.

According to a New York Times article written in late November, the government had at that point already spent $1.4 trillion and committed $8 trillion on various baiout efforts. This latter number is equivalent to 58% of our annual GDP (which was $13.8 trillion in 2007) and is almost certain to grow. Whether these are “expenditures” vs. “investments” and whether this distinction matters is outside the scope of this article. These numbers are cited here to indicate the vast magnitude of the government efforts already underway.

It’s very clear that our fiscal and monetary leaders are willing to do whatever it takes to head off deflation, and that any rule or convention that gets in the way is summarily tossed out the window to the cheers of onlookers.

What’s more amazing is that these radical and exceptionally aggressive reflation attempts have taken place in response to a minor decline in consumer prices and no decline at all in the money supply. The graph below shows that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has indeed fallen, but that it has neither fallen very far nor for very long.

Moreover, the vast majority of the decline to date has taken place as a result of a sharp drop in energy prices. The next graph indicates that there has not been any notable decline in the CPI net of food and energy prices. I am baffled as to why falling energy prices are considered to be a bad thing for the US economy, but that’s a topic for another article. The point here is to illustrate that there is as of yet very little in the way of widespread price deflation.

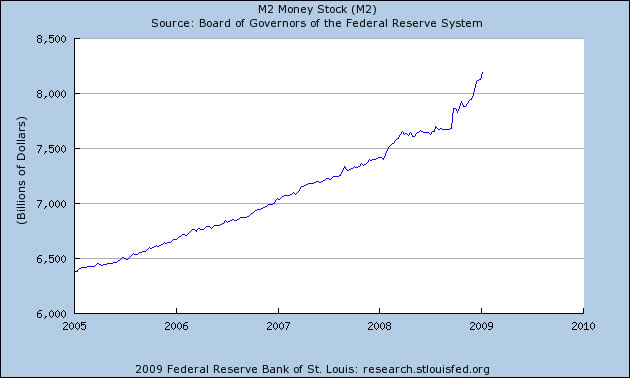

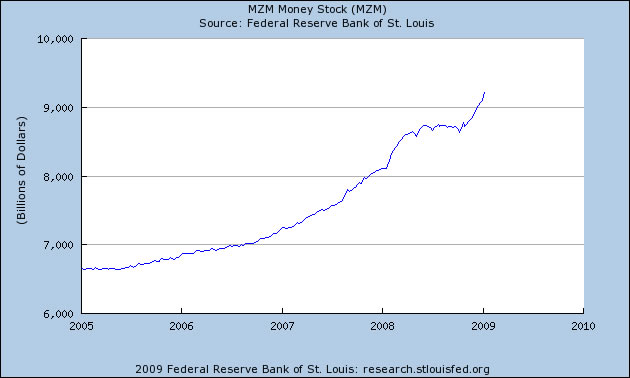

The price declines so far have been fairly minor and very narrowly based, but they do qualify as price deflation. Monetary deflation, on the other hand, is a no-show. The next charts display the money supply as measured by M2 and MZM, the two broadest measures of money supply provided by the Fed. Both measures show that while money supply growth did flatten out earlier in 2008, it has since picked up again in a robust fashion.

Of course, these are backward-looking indicators, and there are reasons to believe that the economic downturn may exert more price-deflationary pressures in the future. But the violence of the government’s reaction to the so-far mild consumer price deflation and a temporary flattening out of monetary growth just goes to show how committed they are to preventing a serious deflation from getting underway.

Why The Government Wants to Inflate

It’s clear why our government is so desperate to prevent deflation from getting a foothold. For reasons I described at the beginning of this article, conventional wisdom holds that deflation is, to quote Bernanke’s 2002 speech, “highly destructive to a modern economy.” Deflation is also seen as being self-reinforcing. Therefore, the mainstream economic view is that deflation — being both highly destructive and self-reinforcing — must not be allowed to take hold, lest the economy be dragged into a deflationary downward spiral from which it is difficult to emerge.

Whether this view is correct or not is immaterial here. Right or wrong, this is the mainstream view on deflation and policymakers will act accordingly. The idea that deflation becomes more powerful and intractable the longer it goes on leads to an extreme policy stance which holds that deflation must be preemptively vanquished at all costs, and that the inflationary effects of such policy are something to worry about later.

Regardless of the economic framework employed, one thing that’s beyond doubt is the fact that the US is heavily indebted, with much of this debt owed to foreigners. Deflation hurts debtors by increasing the real value of their debt burdens. Conversely, inflation helps debtors by magically paying back some of the real value of their debt via currency debasement.

For a long time, our policymakers have bent over backwards to soothe any short-term economic pain, regardless of the long-term problems this caused. The monumental stimulative efforts underway are a clear signal that this hasn’t changed. In this political climate, it is exceedingly difficult to believe that policymakers would allow a prolonged deflation given that such an outcome would help our foreign creditors while inflicting economic pain on the over-indebted American voting populace. Politically speaking, it’s much easier to allow inflation to eat away at the real value of that debt. Inflation is additionally the most politically viable way for the government to pay back its own massive debts without having to resort to tax increases or spending cuts.

There is a powerful combination at work. Mainstream economic pundits, academics, and policymakers are united in their opinion that deflation must be prevented. They are providing a theoretical justification for highly inflationary policy, and right or wrong, this justification is widely accepted as truth. Meanwhile, from a politician’s standpoint, inflation is a far more viable and easy path than deflation. This combination of real-world incentive and theoretical justification induces our monetary and fiscal leaders to overwhelmingly favor an inflationary outcome.

The Government Will Inflate

The evidence certainly suggests that the government is extremely committed to preventing deflation. But there is no need to guess, as the sweeping reflationary policy already enacted over the past several months shows this to be the case. The US government will act as necessary to prevent a protracted deflation from taking place. The pure fiat currency system, combined with the prevailing wisdom that deflation must be prevented at all costs, allows them to do so.

Again, I am not arguing against the fact that there are powerful deflationary forces in play. There are. But a government with a printing press and a virulently anti-deflation philosophy is an even more powerful force.

There are lag times between government action and economic reaction. The deflationary forces may hold sway for a while yet. But as long as that remains the case, the government will respond with ever more desperate and radical reflationary policy. This is because the government and the Fed are reactive rather than anticipatory, as their conduct throughout the credit bubble and its aftermath have demonstrated beyond doubt.

To the extent that their desired inflation is not yet taking place, they will feel obliged to take even more dramatically inflationary steps. They will not stop until they get feedback that inflation is well underway and that deflation has been safely vanquished. By the time that happens, the lag times dictate that it will likely be too late to effectively reverse the inflationary aftermath of their policy.

It’s not clear how long the deflation scare will last, but I strongly believe that the longer it lasts, the more extreme the government policy will get, and the more dramatic the eventual inflationary overshoot will be. The deflation thus sows the seeds of its own violent demise.

Under the current system, with the current set of people at the helm, a protracted deflation is not much of a threat. The far more real danger is that the government’s extremist policy and pro-inflation bias will lead to a serious loss of dollar purchasing power at some point in the future.

Editor’s Note: Read Part II: “Counterpoints.” Rich may also respond to (or otherwise parry) your questions, concerns or challenges in future posts. So feel free send him an email at rtoscano@pcasd.com with your thoughts.

— RICH TOSCANO