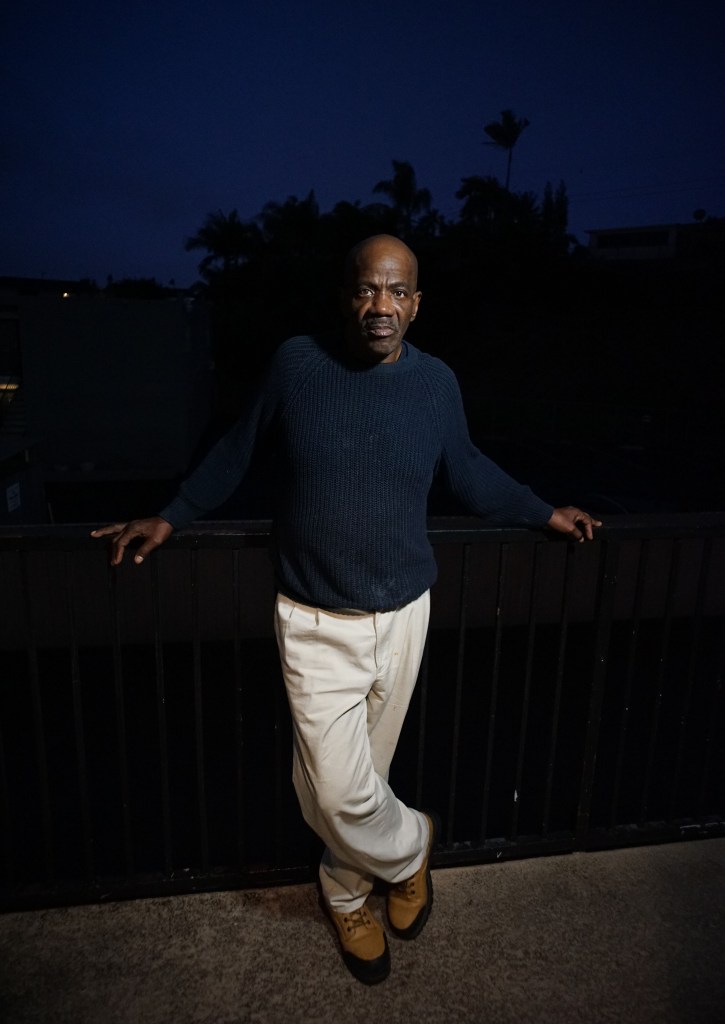

Early one December morning, 62-year-old Edward lay in the grass next to a utility box steps away from Scripps Mercy Hospital’s emergency room. He shivered as he tried to sleep.

A walker lay flat on the grass beside him. Atop the utility box was a purple plastic hospital bag, a bus pass and his hospital discharge paperwork from the night before.

Edward is one of thousands of homeless San Diegans pouring in and out of local hospitals – and in many cases, being discharged without shelter or a safe place to recuperate. Homeless service workers and neighbors have spotted homeless residents like Edward, sometimes still wearing hospital wristbands, socks and gowns, on the streets.

Voice of San Diego spent months digging into why this happens and tracking the experiences of homeless patients and people tasked with trying to help them.

State data crunched by the county shows about 11,550 homeless residents departed local hospital ERs in 2021, the most recent year where data is available.

Federal law requires that hospitals treat anyone who enters an emergency department. But hospitals are designed to swiftly treat immediate emergencies – not to address the ongoing complexities of homeless patients’ lives and how those complexities impact their health.

Hospital staff don’t have hotlines to call that can immediately deliver places for their homeless patients to go after discharge. Beds in shelters and other facilities are often elusive, especially after business hours. Hospitals are left to navigate on their own. Sometimes they do find places for their homeless patients.

But the absence of on-call resources for hospitals often hurrying to discharge still-vulnerable patients they have decided no longer need hospital-level care has become more glaring since a five-year-old state law mandated that hospitals prioritize shelter placements for homeless patients.

Many fragile patients return to the conditions that caused or exacerbated their illness. Infections return or worsen, organs fail and mental health challenges persist. The result can be devastating for homeless San Diegans – and at very least, demoralizing.

Some homeless patients experience this repeatedly. State data showed homeless residents who departed San Diego County ERs in 2021 had an average of three discharges.

Edward’s December discharge paperwork from Scripps showed he was released to his “previous dwelling location” the night before I met him after treatment for generalized weakness. Edward is HIV positive and was diagnosed with malnutrition, according to the paperwork that included phone numbers for shelters and other resources. Voice of San Diego is only using Edward’s first name.

Edward, who didn’t have a cell phone, couldn’t call them.

“I’ve been given that list so many times,” Edward said.

Leaders at Scripps Mercy Hospital, like other hospitals in the region, say they try to link homeless patients with more direct connections to post-hospital options whenever they can. When those aren’t available, Scripps says homeless patients can sleep in the Hillcrest ER’s lobby overnight if they “meet the basic requirements for good behavior.”

Edward didn’t say whether he was offered a chance to sleep in the ER lobby, which he described as chaotic and uncomfortable.

State data doesn’t clarify how often homeless San Diegans end up sleeping outside after a hospital visit. The state, which regulates hospitals, also doesn’t track what percentage of homeless patients landed in shelters or recuperative care facilities designed to serve them.

That means much of what’s publicly known about the aftermath of homeless patients’ hospital visits is anecdotal – and there are lots of anecdotes.

Homeless service providers say newly discharged homeless patients regularly show up at the city of San Diego’s downtown Homelessness Response Center to line up with others seeking shelter and patients sometimes appear at other facilities reporting that hospitals sent them to access resources that often aren’t available.

“We’re seeing at least several each week coming with their plastic hospital bag and booties and whatever they have, and coming right from the hospital to here,” said Angie Striepling, director of housing initiatives for PATH, which operates the downtown center.

On a Monday morning in December, 16 people gathered outside the downtown center. Three told Voice they were recently at local hospitals – and each left without a shelter bed. Only one person in line that morning got a bed.

…

A state law that took effect in 2019 requires that hospitals establish plans for discharging homeless patients and try to link them with shelter or other options that could keep them returning to the street.

The law, SB 1152, increased hospital tracking of encounters with homeless patients and offerings such as food and weather-appropriate clothing, but it didn’t fund new shelter beds or other post-hospital options. As a result, there hasn’t been a dramatic increase in resources.

Meanwhile, hospitals are seeing more homeless patients.

UC San Diego Health reports the number of homeless patients it served at its Hillcrest hospital nearly tripled from 2019 to 2022 and the number of visits by homeless patients spiked 82 percent. During the same period, Scripps Mercy Hospital said its inpatient and ER discharges of homeless patients at its Hillcrest hospital spiked 55 percent though the number of homeless patients increased by a smaller 13 percent.

The increasing vulnerability of San Diego’s homeless population is fueling those trends. The populations of homeless seniors and people with disabilities sleeping on the street for at least a year have skyrocketed. Drug overdoses have also surged.

Some homeless patients, like 60-year-old CeCe Hughes, depart the hospital only to return days or even hours later. During a two-week period this fall, Hughes ended up in local ERs throughout San Diego seven times with multiple ailments – from stomach pain to a fall injury.

On one occasion, she left against medical advice and quickly regretted it. She sometimes spoke with hospital social workers about resources, but never got an immediate place to stay.

Hospitals say they work to try to connect patients with shelter and other services when it’s time for them to depart but acknowledge they often face roadblocks. For example, hospitals can’t directly refer patients to city-funded homeless shelters and must rely on service providers to make those connections.

The increasing pressure hospital staff have faced the past few years to discharge patients as soon as possible to make room for others can clash with efforts to find safe destinations for homeless patients.

“The constant theme is, ‘They’re medically cleared, get them out,’” said Stanton G.K. Otero, a former UCSD medical social worker who until departing in June regularly sought shelter and other post-discharge options for unhoused patients preparing to leave the Hillcrest hospital.

Otero said rushed discharges sometimes led to homeless patients returning within a couple days. Otero said he often tried to persuade doctors and managers to hold unsheltered patients an extra day or two to give them more time to recover and secure a safe place for them to go. He wasn’t always successful.

Service providers often get calls from hospital staffers like Otero hoping to quickly connect someone with shelter, treatment programs or other housing options.

Jeannine Nash of Serene Health, a company that connects patients struggling with homelessness or housing insecurity with services, recalled a 5:22 p.m. call from a local hospital in November asking if she could link a homeless ER patient with an independent living facility. It was too late for the woman to go to the bank to withdraw money for rent and a case manager told Nash it wasn’t clear they could keep the woman in the hospital overnight. Nash said the hospital she declined to name ultimately discharged the woman, who didn’t a cell phone. Nash never heard from her again.

Hospital officials say their teams carefully assess homeless patients’ conditions before discharging them and try to connect them with resources but also must balance those efforts with the need to ensure other patients can swiftly access care. They argue there’s a need for more services outside their doors to support homeless patients.

“Across the region, hospital capacity is in extreme high demand, and patient beds need to remain available for the critically ill,” UCSD Health spokeswoman Michelle Brubaker wrote in a statement.

“Local health systems need reliable community support for unhoused individuals after hospital-level care has been provided, so that medical teams can address others awaiting treatment for conditions, such as heart attack, stroke or traumatic injury.”

Scripps reports a countywide lack of immediate post-discharge options for homeless patients and others with complex needs including behavioral health patients led to a 186 percent spike over the past four years in days patients deemed medically stable remained in its hospitals because they didn’t have a safe landing place. Sometimes hospitals are waiting for insurance companies to sign off on step-down care options for patients, or for longer-term care beds to open up.

Other times, hospital staff and insurers decide patients’ conditions don’t merit a longer stay in the hospital, particularly when others are waiting. Homeless patients can also decide – as Hughes once did – that they don’t want to remain in the hospital despite doctors’ advice they remain, or decline offers of step-down care or shelter they decide won’t meet their needs. They don’t always understand the implications of their answers and end up back on the street before they are ready, still feeling weak and disoriented.

That’s how Hughes felt after a late fall visit at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Hillcrest during a time when she typically slept outside the downtown Homelessness Response Center. She reported that she tripped over her walker, injured her hip and was unable to get up just before 5 a.m. on Oct. 31.

When Hughes arrived at the hospital, records show Hughes – who has diabetes and hypertension – was drowsy and appeared to have sleep apnea issues that led a doctor to admit her. The next day, Nov. 1, Hughes met with a social worker who wrote that she had declined help finding an independent living facility to move into as she expected to have a place to stay come Nov. 3. She was “cleared for home (discharge).”

But Hughes said she was caught off guard when Scripps Mercy pushed her out the next day. She left the hospital on Nov. 2 with a list of phone numbers and addresses for shelters and other community resources. Hughes’ discharge paperwork said she’d return to her “previous dwelling location.” Hughes said she was not offered a shuttle or help getting to a bus stop though records show a hospital staffer initially used a wheelchair to help her outside before leaving Hughes with her walker.

Still disoriented and weak, Hughes struggled to make her way back downtown after she was forced to leave the hospital.

“I’m having trouble walking to the bus stop,” Hughes texted me at about 11:45 a.m.

Hughes, exhausted and confused, sent another message 42 minutes later saying she had yet to make it to one of the bus stops within a few blocks of Scripps Mercy.

At about 12:40 p.m., Hughes said she was sitting down again. Her knees hurt. Just after 1 p.m., Hughes said she couldn’t walk any further.

“I have no idea where I’m at,” Hughes wrote.

Hughes later told Voice she ended up sitting under a large tree a few blocks from the hospital as she tried to get her bearings.

By 4:25 p.m., Hughes said she’d found a bus but wasn’t sure she was on the route that would take her back downtown. Hughes said she didn’t make it to back to the Homelessness Response Center until the next day.

In response to questions about Hughes’ discharge, Scripps Health spokesman Keith Darcé wrote in an email that once a medical provider determines someone is stable enough for discharge, the team evaluates whether the patient can independently handle activities such as using medical equipment to walk on their own and can explain how they’ll get basic resources.

“If so, it is possible for a patient to have a non-acute health issue or mental illness and be homeless and still be able to be discharged from the hospital setting,” Darcé wrote.

For George Moore, 65, a series of visits to UCSD’s ER during a roughly six-week period escalated into a more terrifying experience. Moore’s story reveals how common health conditions can mushroom.

On Feb. 1, records show hospital staff fitted Moore with a catheter at UCSD Medical Center in Hillcrest after he came to the ER describing pain and struggles urinating. Moore, who lived on the street downtown and for a time stayed in a shelter, lacked another immediate option to address symptoms that alarmed him. He ultimately returned to UCSD’s ER eight times over a 42-day period with concerns about the catheter he struggled to maintain on the street and in the shelter.

A couple days after he got the catheter, Moore saw blood in his urine. An ambulance brought him to UCSD’s ER again. He was diagnosed with an inflamed bladder and prescribed an antibiotic. The following week, Moore returned begging to have the catheter removed but a doctor said he’d need to see a urologist first. Moore eventually booked an appointment in late March. On Feb. 11, hospital records show Moore resurfaced with a leaking catheter and pain from a clot. He left about 24 hours later with a bus pass and clean pants to replace those he’d soiled. Then a CT scan during a Feb. 23 visit revealed Moore had a “very large prostate,” according to hospital records. After returning to UCSD on March 8 with darker urine and “bright red” liquid in his catheter tubing, Moore was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and an inflamed prostate.

At the time, Moore feared he wasn’t going to make it. Moore’s father died of prostate cancer and after a series of ER visits that left him with little understanding of what was wrong, Moore worried he might suffer the same fate.

Moore said he implored hospital staff to admit him.

“Why can’t I just stay and figure out what’s really going on inside me?” Moore recalled pleading.

Moore said he continued to struggle with the catheter after he moved into a shelter that he said limited the time residents could spend in one of the facility’s few restrooms.

On March 11, hospital records show Moore arrived at UCSD’s ER dealing with leakage from the catheter and told hospital staff he was considering trying to overdose on fentanyl because he was “smelling like urine” and embarrassed to be around others at the shelter. Records show Moore was cleared for release from the ER 10 hours after he arrived. Hospital staff planned to give him 14 days of medication, clothes, a snack and a bus pass.

“They didn’t take me serious,” Moore said. “They didn’t show that much compassion at all.”

By March 17, friends encouraged Moore to go to the Homelessness Response Center to seek an advocate.

That’s where he met Janis Wilds of the nonprofit Housing 4 the Homeless who said Moore appeared disoriented and unsteady on his feet. Moore showed her his dirty catheter bag filled with bloody, discolored urine. Wilds said she asked Moore if she could call 911 and accompany him to the ER.

Things went differently when Wilds joined Moore at the hospital. Tests revealed Moore’s infection was resistant to the antibiotic he’d previously been prescribed, and he got a new prescription. Hospital staff also noted in records that since Moore was homeless and having trouble caring for himself and his catheter, he would see a physical therapist and a case manager who might help the hospital place him elsewhere to recover.

The next day, Moore moved into a skilled nursing facility. Months later, he’s taking medication that has allowed him to stop using the catheter and recently moved into his own apartment.

Brubaker of UCSD Health declined to comment directly on Moore’s experiences in the ER, citing a federal privacy law, but said there are “myriad variables” to be assessed during every visit.

“What is constant, however, is the commitment of the UC San Diego Health clinical teams to care for the needs of all patients who present to us in our hospitals and emergency departments,” Brubaker wrote.

Indeed, federal law requires hospitals to examine, treat and provide emergency care to patients who appear within 250 yards of their facilities until they’re deemed stable even if they don’t have the resources to pay for that care. Hospital policies and the nuances of the law determine how this works in practice.

A situation Voice witnessed on a Friday evening in early September illustrates the moral quandaries that emerge when policies like this collide with the complexities of the homelessness crisis. Hospital staff can deem vulnerable people caught up in the crisis challenging patients. They still need care – and often repeatedly.

At about 9 p.m., Voice looked on as a woman with ashen skin and a shaved head lay spread eagle on the bumpy yellow crossing mat across the street from the Scripps Mercy ER entrance. It wasn’t clear she was breathing.

Volunteer nurses working with Housing 4 the Homeless, which does outreach in Hillcrest and downtown, ran over to check her vitals. ER discharge paperwork printed about 40 minutes earlier lay nearby. The document said the woman, whom Voice is not naming, had been treated for an altered mental state and diagnosed with drowsiness, transient altered awareness and hypothermia.

After the woman opened her eyes and began to writhe around as if in pain, nurse Laura Chechel called out to Scripps’ security asking if they could get her into the ER. A security guard yelled back that the patient had left against medical advice and ran around the facility naked prior to her departure. The woman was now wearing sweatpants and a long-sleeved shirt. The guard said management told him someone needed to call 911 as the woman was now across the street from the ER. Chechel and another nurse ultimately helped the woman walk to a wheelchair that security rolled outside for her near the ER entrance across the street.

When Chechel returned to the ER later, she said a hospital staffer told her the woman had been given a bus pass earlier. The woman remained in the ER lobby.

Chechel later said she was discouraged by how the situation played out.

“Let’s work together collectively to figure out what is going on here instead of, ‘I’ve called a supervisor’ and someone else comes out and says, ‘You’re gonna have to call 911,’” Chechel said. “It’s disappointing.”

In response to questions from Voice, Scripps Health spokeswoman Janice Collins declined to elaborate on the specific incident but wrote that the hospital system doesn’t consider the federal law to be triggered if someone appears on public property such as a sidewalk. She wrote in an email that that the health system considers the law to apply within a 250-yard radius – on its own property.

Still, Collins wrote in an email, security guards check on people who appear to be having medical issues.

“While privacy laws prevent us from speaking to specifics of any patient case, what we can say is that if our security guards see someone outside our property who could be in medical distress, they ask that person if they need help and if they would like them to call 911,” Collins wrote. “It is the person’s prerogative to decline that offer if they wish.”

Our group has had many, many reports of the neglect of homeless people at Scripps Hillcrest. They are notorious for discharging homeless people in the middle of the night when there are fewer people around to object to someone being kicked out to the street with just a hospital gown on for clothing.

We have worked with Housing 4 the Homeless and Janis Wilds in the past with homeless patients, they are wonderful, caring people. If a homeless person is to receive proper care they seem to need a personal advocate who is willing to go to the hospital and get in the doctor’s faces and say to them “This is a dangerous discharge, you cannot kick this person to the street as they are now.”

It can take a day or two in order to find a bed for step down care, the homeless person also needs follow up in the step down facility to help see to their needs and to make sure they stay long enough to get well. It is a very labor intensive process and our healthcare system is not set up to deal with the unique challenges of caring for the homeless.

We are failing the people on the lowest rung of our society. The attitude seems to be “Do the minimum needed, then get them out. They are dirty, nasty and non-compliant. I want them out of my facility.”

Our group has had many, many reports of the neglect of homeless people at Scripps Hillcrest. They are notorious for discharging homeless people in the middle of the night when there are fewer people around to object to someone being kicked out to the street with just a hospital gown on for clothing.

We have worked with Housing 4 the Homeless and Janis Wilds in the past with homeless patients, they are wonderful, caring people. If a homeless person is to receive proper care they seem to need a personal advocate who is willing to go to the hospital and get in the doctor’s faces and say to them “This is a dangerous discharge, you cannot kick this person to the street as they are now.”

It can take a day or two in order to find a bed for step down care, the homeless person also needs follow up in the step down facility to help see to their needs and to make sure they stay long enough to get well. It is a very labor intensive process and our healthcare system is not set up to deal with the unique challenges of caring for the homeless.

We are failing the people on the lowest rung of our society. The attitude seems to be “Do the minimum needed, then get them out. They are dirty, nasty and non-compliant. I want them out of my facility.”

Great article, Lisa, thank you for spotlighting this dilemma.

Peggy makes such a impact with her photography.

We have these conversations daily at TACO with our clients , who are struggling with medical issues.

The frustration I feel when they leave a hospital setting AMA and then ask if they can sit in my office to do their breathing treatments for COPD when they need to be in the hospital or when they ask for a grocery bag as a substitute for thier colostomy bag! Ultimately we call 911 and back to the hospital they go.

My phone rings all day, calls from caring social workers at the local hospitals, asking if we are a shelter (were not) and if we have space for a patient who is soon to be discharged. I then spend an additional 20+ minutes recommending other resources.

My best experiences have been when I have taken clients myself to the hospital, advocating for them, answering questions with them, repeating questions so they understand what is being asked – having the hospital see someone cares for this human being and we are here to get the help we all deserve!

More recuperative care units are needed!

Thank you for caring for this community of humans.

Susan Fleming

Executive Director

Third Avenue Charitable Organization (TACO)

We wish you would find a real job to occupy your time instead.

Sincerely,

All of your neighbors

36000USD In Month. Online Jobs New Best Jobs For You. Start Your Good Career With Them. qg Its Very Simple For EveryOne. Position open to candidates located anywhere in USA, UK, AUS, NZ And CA These Countries.

Here Go…… https://OnlineCareerJobs4.blogspot.com

Why isn’t VOSD taking these people in and treating them in their corporate offices? There is clearly a need , I think you should pay for it.

I agree, they should be in jail instead of clogging up hospitals and delaying real people from getting care.

“…delaying real people from getting care.”????? We are all a few degrees away from needing other humans to help us.

Mental illness & homelessness can affect anyone. I’d be careful how you talk. You’re perpetuating the stigma of mental health.